One of the places where I most actively write is my Letterboxd blog, where I write reviews, blurbs, and notes almost daily on films new and old. As I edit a forthcoming review of the new film JANET PLANET, I wanted to share my top ten personal favorite reviews of films released in the first half of 2024, arranged in chronological viewing order. Hope you enjoy.

THE BOY AND THE HERON (dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

Definitely a cousin of Spirited Away, a more somber and uncompromising take on the Alice in Wonderland-esqe story that Miyazaki excels in telling; this leans toward the personal reflection of The Wind Rises rather than the wonderous innocence of Spirited, less concerned with crafting a universal fairy tale than reckoning with imperialism, his body of work, and trauma.

Mahito is rendered with a stone faced anger, rarely crying or expressing shock at what's happening. He accepts this world and its rules, even when its not clear to us, which it rarely is - I didn't entirely mind the flowing, unexplainable nature of the story, but the lack of build-up for certain beats seemed to reduce the power of these moments. It's thus tempting to view the entire story as an expression of individual struggle, a boy's magical journey through his self and his past, trying to unpack the legacy of his country and family (seen most clearly through his father's war profiteering and the fascist symbolism of the Parakeets).

The journey itself is absolutely gorgeous, though, defying time and space in a wonderous flow of scenes and encounters. What all these places have in common, however, is a distinct push-back against recognition and connection, as few of the creatures and denizens speak to Mahito or attempt to exist in harmony: they ignore, attack, destroy, and consume. Mahito, perhaps, is truly understanding the selfishness and senselessness of the world, trying to find love and care amongst chaos. We never feel safe or comfortable, with a fantastic tension between the wonder and the danger.

Miyazaki's films have always felt like separate worlds to me, ones that would exist whether I was watching them or not. When this film ended, it felt like I had watched one of these worlds die, imploding into color and light.

FALLEN LEAVES (dir. Aki Kaurismäki)

Love is real and alive in Finland. Went into the theater in a bad mood and left feeling absolutely joyful, smiling all the way home; during its run, however, I was wracked with anxiety from all the fateful moments that kept the protagonists further and further from each other, though hoping that all this struggle would make the final love feel earned. And it did! Importantly, though, Kaurismaki creates two different obstacles: the accidental ones that feel whimsical (a phone number lost in the wind) and the ones that come from the characters' flaws that cannot be simply overcome (alcoholism). To find love in such dismal, arduous, working-class surroundings, hearing only news of distant wars and old songs, we must keep searching, keep walking against the winds trying to blow us back, and impossibly fix ourselves as we do so. Only then are we allowed to walk into the sunset with a dog and someone who loves us because and despite of who we are.

THE ZONE OF INTEREST (dir. Jonathan Glazer)

At the risk of sounding hyperbolic, I prayed on my way home from this movie. It felt like the only natural conclusion to the journey I had been on since the opening soundscape, which pulled me into a world where we are given uncomfortable proximity to evil, to horrors both immediate and just out of sight. After the credits finally ended, I wanted to scream, cry, lash out, lay down, never watch it again, and go to the next possible screening. I didn't do any of those things, instead just hyperventilating in the bathroom for a second before leaving the theater.

For the first stretch, I struggled to fully appreciate what was happening, feeling like, in that first half hour, I'd gotten the point of what Glazer and his team were trying to do, and wondered what other banalities they could show to hammer their point home. But there are brilliant moments (the night-vision, Mica Levi's score, the flower sequence, the piano) that show Glazer's understanding that our attention decays over time, that we grow used to atrocities. Without hitting us over the head, he brings us back to the moment, brings us closer to the Hoss family.

They are a family that is deceptively ordinary, a characterization accomplished through the surveillance style filmmaking and improvised dialogue. An interesting bit of historical context is that they were originally working class, taking advantage of the genocide to climb the ranks of class; it is not some abstract idea that created their rabid desire to create a bourgeois life next to a concentration camp, but a system that is built on occupation, destruction, murder, and theft.

These types of people do not only exist in the past. Glazer and the two leads have created a ritual, using film to recreate history and live, for a short while, with evil. We live, too, with their daily routines so we can understand how evil is not obvious, and how one's humanity and universal emotions (his goodbye to the horse, for example) do not excuse their actions. It's terrifying to be so close to Nazis, and even more terrifying to realize they live next to us, and that years of state propaganda have left us just as apathetic to the screams around us. It's a film that is both allegory and historical document, without sacrificing any immediacy nor urgency.

Genocides do not just happen. They are planned and carried out by people, individuals who know exactly what they are doing. Their plans and actions of mass murder do not come from a lack of understanding of their victims or distance from the culture and humanity. They are living on the land they denigrate, occupying a place and people that they hear the screams of, that they kill with their own hands. It is not a stretch to compare 20th century German antisemitism to the Islamophobic and xenophobic propaganda spread by the modern American state, the rhetoric that tells the public not to turn a blind eye to the killings in Palestine, Afghanistan, Iraq, and every other country the state has occupied, but to cheer it on, to support it. They have dehumanized the people they take everything from. Everything but their indestructible ability to resist, to be free.

To risk being hyperbolic one last time, this is monumental, a work that represents both specific and universal ideas of war, capitalism, prejudice, occupation, and genocide. It stands at a distance, but it invades your body. It doesn't let you go.

THE PEOPLE’S JOKER (dir. Vera Drew)

Watched as Vera Drew hopefully intended - in an near-empty arthouse theater, slightly hungover, holding hands with another beautiful trans girl, on the verge of crying for almost the entire thing. Really something special, big stuff going on here.

ALL OF US STRANGERS (dir. Andrew Haigh)

This review contains spoilers.

Nothing could have prepared for me this. Not the trailers, not the source material, nor any of Haigh's previous movies. This is a film that is indescribably brilliant in terms of tone, atmosphere, and emotion, less a film than a pitch perfect recreation of a dream, hyper realistic but just slightly surreal, the kind that makes you wordlessly sad when you wake up, as if you've lived an entire life and death in the few hours you were away. It contains tremendous, terrifying power, and, for the last half, I forgot I was watching a movie at all. The actors became their characters and the camera faded away. It was transcendent and terrifying.

How did Haigh and his team create this world out of a concept that easily could have been trauma porn, a sentimental weeper, or eye-rolling wish fulfilment? It's mostly through containment: there are only four characters in the movie (besides a few ghost-like extras drifting around the edges), and thus our entire world is hinged on the central relationships that are explored in brief scenes that Haigh doesn't fully explain. Most of them are fleshed out by the performances (90% of this movie, I think, is close-ups of Andrew Scott's face), and we fill in the blanks ourselves, with our own ghosts and experiences. I remember my mom telling me that, when I was about 3, she looked at me and knew I was gay. I remember the confusion and pain and empathy and love that defined our conversations when I came out as trans. I remember.

Haigh pulls no punches; we get no respites, no breaks, no resolution that would let us off the hook and allow us to take a breather in a less lonely place (the motif of false awakenings only adds to this). We must stay here with Adam and confront the most painful and cathartic experiences life has to offer. The story beats are never obvious, and the way they unfold with intimacy and strangeness adds another shimmering, ephemeral layer to the whole thing.

The ketamine sequence is one of the more memorable scenes, upending the style while tapping into the existential fear that strikes like a viper in our most treasured, beautiful moments. I remember the moments where I've been dancing in the club, the one I've been looking forward to going to all week, pressed against someone endlessly sexy and beautiful, and thinking "is this it?" Will these people fade and become less interesting? Do these moments make up for the pain of life? Do they only become powerful in memory? I want to remember. Go to another party, and hang myself, gently on the shelf.

This isn't to say that there isn't hope here - it just isn't easy hope. It's realistic and painful and open-ended, choosing to fade into the stars over giving us somewhere safe to land on Earth. What makes the ending, which I initially wanted to stop as soon as it started, not cruel is that it's framed not as tragedy, but as something, again, transcendent and metaphysical; Harry was not bound to be Adam's love forever, but rather a stepping stone to a future where Adam, who lost the people he thought would love him forever, can live with the knowledge that he is capable of love and being loved. We don't have to see him move on in a trite scene that a different film would indulge in: we just need to see Andrew Scott's ambivalent, surprising, endlessly layered, and comforting reaction to know that things will be okay. He's waking up and he's in control. It's one of the greatest moments of acting I've ever seen.

Earlier, I wrote that this film is terrifying, and it was. Maybe it still is, but my heart is calmed now, especially after laying with my love together in bed, crying and talking about it as the rain poured outside. It puts you in a place where you must confront grief, longing, and the existential parts of this life, and it makes you search and work for catharsis, but the end result is worth it. It's never cloying or cruel, it's always human, human because we can't figure everything out or ever fully grasp every layer. That's scary and sad, yes, but it's also beautiful. Love recreates us. It's a story that feels like staring into a very human abyss, but, by looking into it for long enough, we begin to see stars.

AGGRO DR1FT (dir. Harmony Korine)

Achieves the honor of being the first movie I've ever walked out of. It wasn't offensive or irredeemably bad, but after the first 40 minutes I thought, "yep. got it. cool." The movie sludges along with no interest in changing, developing, warping, or giving any more meaning to its gimmick. And, yeah, the whole movie is a gimmick, I know this, but if your gimmick is "Playstation-neon-Miami-hitman-stoner-nightmare", it should at least be fun! Maybe its initial strip club screenings would have made for a better viewing experience. But yeah. Excruciatingly boring with nothing new to offer after the first 20 minutes. Is this Korine's prophecy of the future, or a warning?

I SAW THE TV GLOW (dir. Jane Schoenbrun)

A week later, so many thoughts and very few words. It still takes over my body when I think about it. An internal horror movie that, though never saying the word, is absolutely trans in every strand of its DNA.

Its genetic code is a hazy fusion of '90s television/physical media, Cronenberg, and the suburbs, a reclamation of trauma and pain that ends up glowing. Gut-wrenchingly accurate in representing the experience of so many trans people trying to find the worlds that will allow them to exist, experiencing the horrors of home, away, isolation, and connection.

A feedback loop starts: television shows represent the suburbs where you live, and you subsequently look at the suburbs through the eyes of those characters, of that show. You search for the beauty and the mystery that these stories capture, and eventually you look so hard you start to see them. And then you're trapped. Nostalgia and escapism can kill. But I hope this movie reaches the trans people in these spaces and saves them.

"There is still time.”

LA CHIMERA (dir. Alice Rohrwacher)

Spent most of the first half in a mood of mild curiosity - I enjoyed what was happening, but struggled to find a concrete rhyme or reason for the "why" of it all. I started to just let the movie wash over me. Most of my attention was on all the women's names as I tested them in my head to see how'd they fit with my very Italian last name. I'd love for a new name to keep the Italian quality of my current one, but none really felt right. I also admired everyone's noses. Wow, big noses are beautiful. It made me happy to have mine.

Once the second half (beginning with the dance party and the beach grave robbery) kicked in, though, my thoughts stopped wandering. All it took was the beauty of a statue and the beauty of Josh O'Connor's face, a simple shot-reverse-shot of a human and a representation of one, to make everything fall into place. I realized I was watching a movie about apathy and depression, a dreamy, faded capturing of what it feels like to go through life wondering where all the joy went. You repeat the same actions, you smile, you feel some pangs of magic, but then you think about it too much and it all falls away.

It is about going on with life and rediscovering beauty, magic, and reverence. When death gets close you realize you don't want it. You want to live and you want to love. It's a miracle.

THE BEAST (dir. Bertrand Bonello)

Filled to the brim with strange, form-breaking elements, all of which work - it's a relentlessly shifting film, never satisfied, and there is joy in all of the reversals, jarring cuts, mixed-media elements, and other strands of its DNA that make it feel alive. There is one conversation that, though presented casually, feels as if the characters are about to turn and look directly into the camera: they debate over whether art needs emotion, whether emotion is different from sentiment, and if producing an affect is enough. They're talking about music, but they might as well be talking about the film itself.

I didn't feel any stirring emotions, no tears or rage. But my body surged with fear, exuberance, and the sensation of being hypnotized from the opening moments onwards. It was feeling I could not name. This is a long film that never drags, but rather pulses, doubles back, leaps forward, spins in circles, and dances. It is a spectacle that seems as curious about itself as the audience is of it. It is an astounding world in and of itself.

It's a fascinating blend of aesthetics, a collection of three universes who exist besides each other in poetic, not logical sense. The third, which takes up most of the second half of the film, made me feel like I was watching a newly uncovered Lynch movie, Lost Highway by way of Twin Peaks: The Return. Bonello emulates him not through the quirky surrealist style that most associate with him, but by capturing the feeling that surges under his later works, the feeling that reality is about to crack wide open, that a scream is about to shatter the lights and destroy the house. Bonello's Los Angeles is vivid and demented, ugly and beautiful, a dry, sunny facade that is simultaneously funny and terrifying. Bonello's reality is one I love to be immersed in.

The film seemed to end several times before the final cut to black, and when it finally concluded, I didn't know what to do. There were no credits - a QR code appeared on screen that led us there (I don't know if this is every screening or just my theater? Odd). The lights came half up and the ten or so other people shuffled out, silent. I stayed, staring at the blank screen. I stayed for a long time, seemingly unable to move. I looked back at the empty theater. I looked up at the empty projection booth. I listened - there was only silence.

I could have stayed there for hours. I still felt hypnotized, calm, clear-headed. Nobody was there, nobody was coming. Eventually I did get up, but I had to force myself to. My legs felt like jelly. I made my way down the long, dark hallway to the lobby. And I left, but the movie did not.

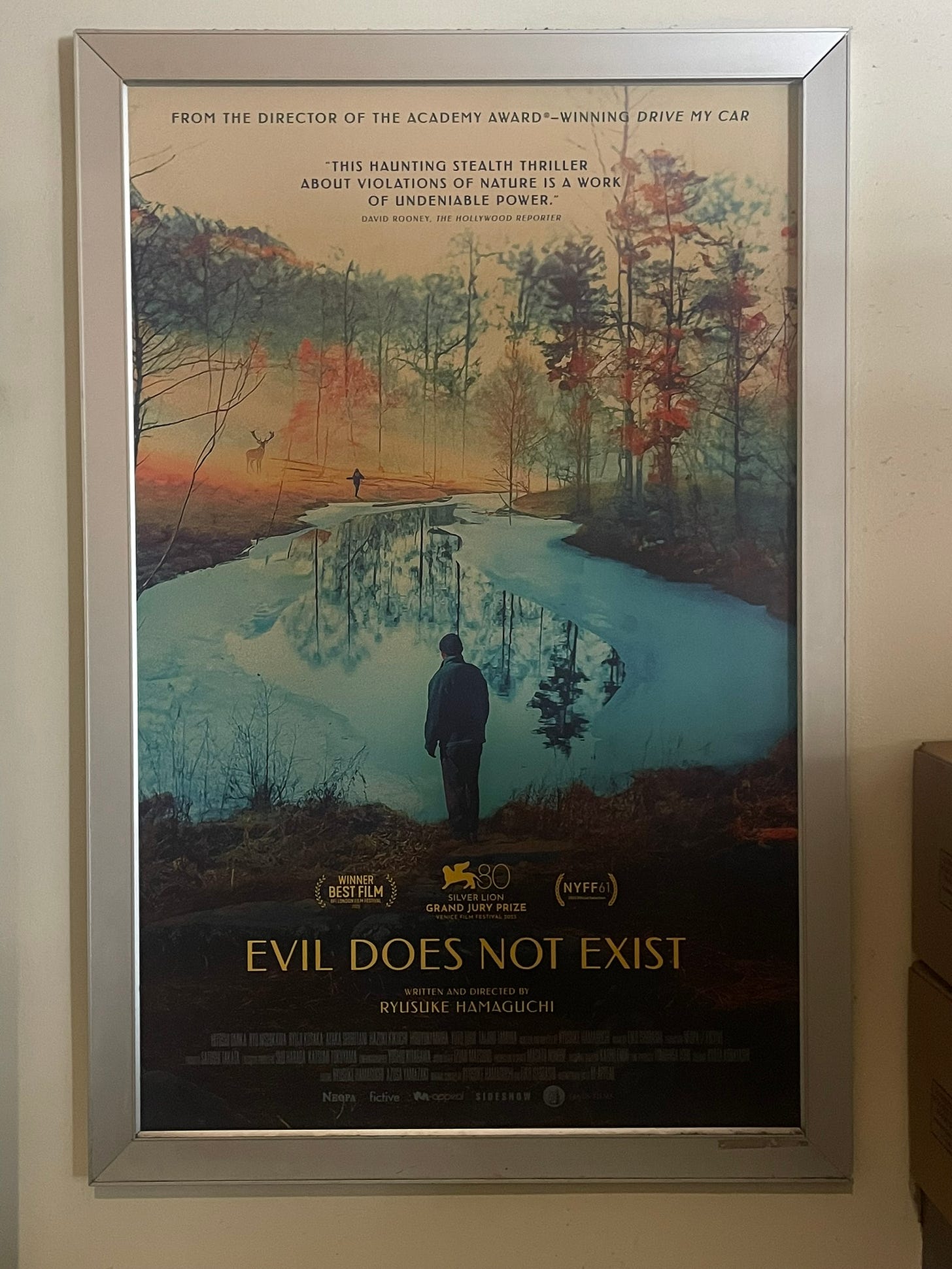

EVIL DOES NOT EXIST (dir. Ryūsuke Hamaguchi)

The spirit of this film is a gut-shot deer. It's beautiful and dangerous, standing in the corner in wariness, but ready to strike and kill if you get too close. It's a mystery in its bones, simply being without attempting to explain itself to us. It's not even sure itself what it is.

We watch it from a distance in a meditative peace. We watch a man chop wood, alone, and then we watch others watch him, strangers to this land who want to know it but could never understand the danger it holds until it's too late. We begin to become a part of this world as we spend more time with the intruders. They don't become evil anymore, only ignorant. We watch all of them smoke, an activity that subtly breaks the "naturalness" of everything else. But it seems like the most natural thing after a while.

It begins with snow and ends in fog. We gaze at trees, towering above us. The deer has run away, and neither of us understand each other better. We're very small creatures, huddled in a dark room, enveloped by a beautiful film. A deer, a spirit, a work of art. A mystery, endless.

And, for the record, THE PEOPLE’S JOKER is the best of the year. So far.